Author: Simon Elias Unteregger

Editor: Dr Johannes J Knecht

An argument frequently articulated in recent years by various voices from politics, the universities and beyond, in the discourse on social justice, is that ‘We are losing sight of the real issues.‘ The prioritisation of identity matters and discourse (identity politics) is said to overshadow significant economic questions regarding wealth distribution and economic inequality, leading to a neglect of genuine problems. Moreover, some minorities and people living on the poverty line often do not have the opportunity to be represented with a strong voice in public discourse. As a result, they are not able to draw public attention to those significant problems. The German politician Sahra Wagenknecht emphasises this point in her book Die Selbstgerechten: Mein Gegenprogramm – für Gemeinsinn und Zusammenhalt, published in 2021. If we want to take the abovementioned critique seriously, we ought to engaging deeply with economic inequality, both globally and within our states and countries. A diligent scientist and publicist, well-suited as a source for insights on the outlined issues, is the Serbian-American economist Branko Milanović

As Milanović (2016) posits: “Calculating global inequality is a relatively recent exercise that began to be undertaken only at the close of the twentieth century.“ (Milanović 2016: 123) Due to various processes like technological developments and historical events, such as the opening of Soviet archives, researchers from the 1990s onwards have been able to access extensive data, allowing for more accurate analyses and comparisons. In his book Global Inequality: A New Approach for the Age of Globalization (2016), Milanović revisits and summarizes central findings derived from his research. After depicting and explaining historical changes in economic inequality both globally and within state borders, as well as our current situation, he extrapolates and discusses trends that can be observed recently, which we will look at in a moment. But let us first have a closer look at the global situation.

1. The global situation

It will come as no surprise that global inequality in average income is very high: we can observe a constant increase from 1820 onward until around 1998. The growing economies of mainly China, but also Japan, India and Indonesia led to a slight decrease thereafter (see: fig 1). However, if those countries are removed from the equation, the inequality would still have increased. Therefore, Milanović introduces the concept of location-based inequality alongside a class-based inequality, first described in economical and sociological studies of the 19th century, most notably the well-known studies by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels (see: Milanović 2016: 125f.; following: M. 2016). The country of origin in which a person is born is the most determining factor in how much they will earn in their professional life. This fact carries significant weight, as Milanović points out that 97% of people live within the country where they were born. In our article on philosophical approaches on equality and justice, we ended with Rawls Theory of Justice. Milanović posits that we need to go beyond Rawls approach (like formulated in his Law of Peoples, 1999), since that approach speaks to justice at the level of the state, and does not include the wider, global picture (M. 2016: 139f.).

But what does this picture show us about the levels of inequality? As Milanović points out, it is primarily the “global middle class” and a very small group of the hyper-rich who have benefited most from globalization (depicted in his well-known “Elephant-Curve”). Take China, for example, where the increase is most evident. Between 2008 and 2011, during and after the financial crisis, “the average urban income in China doubled, and rural incomes increased by 80 percent” (M. 2016: 30). Meanwhile we observe an absence of growth in the “rich world“. Therefore, China now has “a higher mean income (in PPP terms) than Romania, Latvia, or Lithuania“ (M. 2016: 33).

Despite the rapid growth in mean income in some Asian countries like China or India, global inequality is still significantly higher than the within-nation-inequality in the most unequal countries of the world (like South Africa or Colombia; see World Bank’s Gini index) (see further: Hickel, Jason 2018: The Divide. Part 1.1. The Development Delusion). Like mentioned above, Milanović therefore introduces the term “location-based-inequality“ to the discussion “the world where location has the most influence on one’s lifetime income is still the world we live in“ (M. 2016: 131).

Milanović speaks of a “citizenship premium“ alongside a “citizenship penalty,” indicating that, as described by John Roemer (Equality of Opportunity, 2000), “exogenous circumstances” independent of a person’s individual effort—simply the place where one is born—play a dominant role in this person’s future income. We can conceptualize this premium position as a “citizenship rent” (M. 2016: 132), whereby a person is either born with advantages or significant disadvantages depending solely on the place of birth: “there is a ‘premium’ to being an American compared with being a Kenyan at any point in the income distribution” or “just by being born in the United States rather than in Congo, a person would multiply her income by 93 times” (M. 2016: 133).

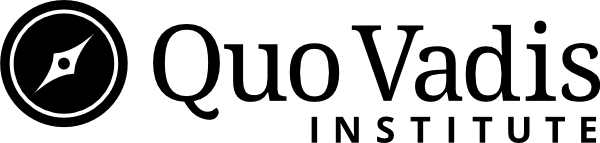

Fig. 1: Global and within-nation inequality (US) (M. 2016: 124)

Like Figure 1 shows, global inequality (measured in Gini coefficients) increased from 1820 onwards. To provide specific numbers: British GDP per capita increased from $2000 in 1820 to around $5000 in 1914, while Chinese GDP per capita decreased from $600 to $550 during the same period. One dominant factor can be seen in the first technical (or industrial) revolution, which led to a tremendous increase in general income in “western countries,” while other countries remained at the same level of income or experienced a slight decrease (M. 2016: 119). Milanović quotes Peer Vries (2013: 46) at this point: “what occurred in the nineteenth century with Western industrialisation and imperialism was not simply a changing of the guard. What emerged was a gap between rich and poor nations, powerful and powerless nations, that was unprecedented in world history.“

Colonialism, among other factors, stabilized and further widened global inequality, until it reached its peak between 1970 and 1980, oscillating “slightly above 70 Gini points“. To provide numerical context: in 1820 “only 20 percent of global inequality was due to difference among countries,“ therefore location based inequality was “almost negligible“, what mattered was the social class into which a person was born within their country of birth – the question revolved around how “well-born“ a person was, not where they were born. But if we look at the data from the mid-20th century the situation had completely reversed: now “80 percent of global inequality depended on where one was born (or lived, in the case of migration), and only 20 percent on one’s social class“ (M. 2016: 128).

The situation depicted above raises another question: if a person can significantly increase their income simply by moving to another country, migration seems like a very reasonable decision. We mentioned that by relocating from Congo to the US, a person would multiply their income by 93 times (depending on the field in which this person works). This figure is even higher when considering countries with comprehensive social systems, such as Sweden. This prompts the question: what position can a person expect when migrating to another country? If they anticipate being in the lowest stratum of a country, nations with developed social systems and low within-nation inequality are a favourable choice, etc. Therefore, let us delve into the topic of migration, for which Milanović has a somewhat unconventional proposal.

2. Migration – An Unusual Approach

Our world is becoming increasingly interconnected – globalization is occurring on many levels. There is an exchange of goods, commodities, information, social networks spanning the globe, allowing all individuals with internet access to participate in these global communities. However, when it comes to migration, tensions are rising, having sparked fervent debates over the past decades. Milanović posits four elementary tensions of migration:

- A tension “between the right of citizens to leave their own country and the lack of the right of people to move wherever they see fit.“

- A tension “between two aspects of globalization: one encourages free movement of all factors of production, goods, technology, and ideas, and another that securely limits the right of movement of labour.“

- A tension “between the economic principle of maximization of income, which presupposes the ability of individuals to make free decisions about where and how to use their labour and capital, and the application of that principle within individual nation-states only, not globally.“

- And finally a tension “between the concept of development that stresses the development of people within their own countries and a broader concept of development that focuses on the betterment of an individual’s position regardless of where he or she lives“ (M. 2016: 147).

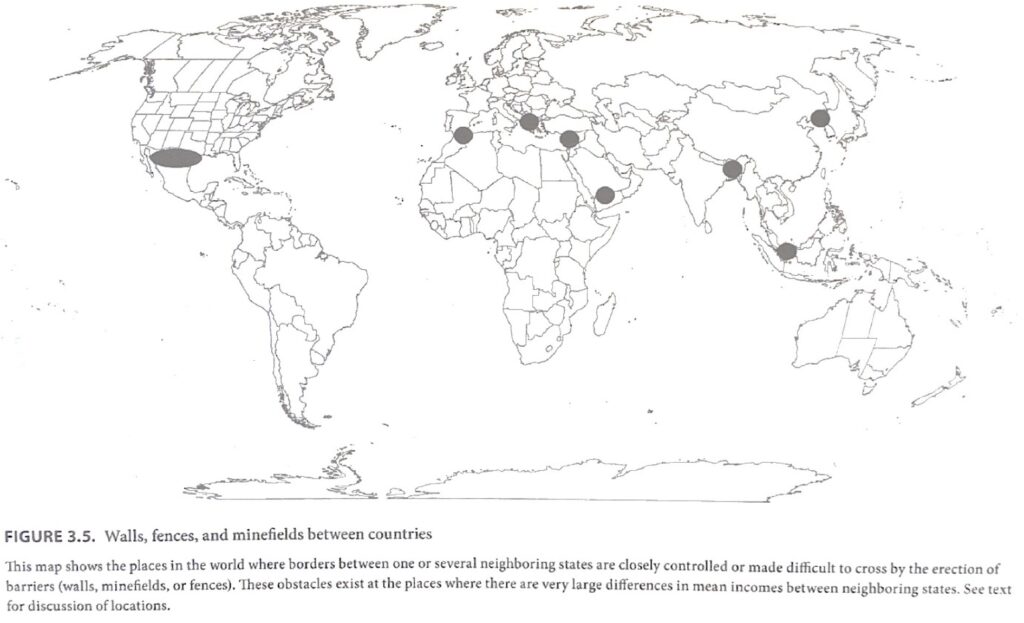

An outcome of these tensions can be observed in the construction of walls and fences, predominantly occurring at borders between wealthy and affluent countries and their less affluent neighbouring countries (as depicted in figure 2). The physical barriers to migration “correspond to the places where the poor and the rich world are in close physical proximity.“

Fig. 2: Walls and fences (M. 2016: 145). Milanović points out „The map was completed just before the upsurge of immigration into Europe in the summer of 2015 and the erection of several new border fences.“

As Milanović argues, the tensions mentioned above are most acute “precisely now“ (referring to 2016), due to the possibility of a global comparison facilitated by expanding globalization. He quotes the economist Simon Kuznets (1958) stating: “Since it is only by contact that recognition and tension are created […] the reduction of physical misery [in underdeveloped countries] permit[s] an increase rather than a diminution of political tensions“ (M. 2016: 148). Therefore, the tensions of migration (leading to political tensions, which we will visit in Chapter 4) were less in the 1980, when global income differences were the greatest, but as mentioned, they are most intense in the present.

Let us look at the situation, out of an economic point of view (the topics strongly touch upon questions of political or practical philosophy, which are set aside at this point). In 2013, around 230 million people (a little over 3% of the world population at that time) were migrants (defined here as: people who were not born in the country where they reside) so “if the migrants created their own country, say, Migratia, it would be the fifth most populous country in the world“ (M. 2016: 149). Milanović points out that according to Gallup surveys (conducted since 2008), “some 700 million people ([…] 13 percent of adults) would like to move to another country.“ The potential stock of migrants is therefore considerably higher, and as Milanović points out, there are few serious considerations in “rich countries“ regarding “how to bridge the gap between the actual and potential numbers of migrants“ (M. 2016: 150).

This brings us to one of the more controversial proposals done by Milanović, which we, in discussing them, do not want to affirm or promote implicitly. However, Milanović’s proposal cuts at a deep question: if the current situation of lacking and eroding public support for migration, the observation that migration is on the rise and will continue to be, and the wish to honour the dignity of each migrant or newcomer proves to be an impossible conundrum to solve: what might a solution be that is more honouring to the person in question?

So let us first trace Milanović’s argument. To introduce his suggestion for migration policy, Milanović refers to a controversial topic: foreign workers in the Gulf countries. He points out that western states think domain focused – meaning that specific rights and privileges can only be enjoyed if one is a part of a “well-defined community“. Western states are primarily concerned with providing “equal treatment to all people living within the country’s borders“ and “discrimination based on a difference in citizenship or residency is considered acceptable, but once a person has become a resident, discrimination within a nation-state is unacceptable“ (M. 2016: 150). Obviously, these rights and privileges are a good in and of itself, but as an experiment, it is this latter point that Milanović wants to probe a bit more deeply: the assumption that any distinction in the treatment of people within a nation is unacceptable, when a migration background is considered.

It is undeniable that the exploitation of labourers from Nepal, India, Sri Lanka, and Pakistan is highly problematic and ethically condemnable. Still, Milanović points out that the question is never raised about the conditions under which these workers must work in their own countries and the wages they receive there, considering they still come to the Gulf states to work. They must perceive the work in the Gulf states as more attractive (of course, the author is aware of the problem of human trafficking, etc. – but new workers can always be recruited). So, the migratory workers, at least many of them, must perceive the salaries and working conditions as better than in their own countries. From a purely economic point of view, the Gulf states are “improving economic conditions for the majority of such foreign workers and their families at home, and [are] reducing global poverty“ (M. 2016: 151).

In view of this, Milanović questions the dominant binary ‘in or out’ position for migrants or newcomers. In this context, ‘in’ means a person benefits from all social structures within a country and has access to all rights and privileges, while ‘out’ means that the state does not provide any care or consideration for this person whatsoever. His questioning of this binary leads him, in a way, to a form of controlled discrimination of migrants for a specific period of time. For example, according to him, three levels of “citizenship rights” could be introduced, whereby a person migrating to a country initially has limited access to the social system, but also could gain more access over time. Considering this approach “would require the willingness of rich countries to redefine what citizenship is and to overcome current anti-immigrant, and in some cases xenophobic, public opinion“ (M. 2016: 154). He makes it clear that his first-best solution to the question of migration and popular support for newcomers would be “free migration of labour” and to “treat all residents equally, regardless of their origin.” However, achieving this goal would require a much greater willingness from both people and governments, and this is, unfortunately, “not the world we inhabit” (M. 2016:153). Therefore, according to Milanović, pragmatic (and less idealistic) solutions might have to be preferred to ensure a balance between sufficient popular support and the protection of the dignity of the migrants, as they are more likely to be implemented.

Considering the eroding popular support for large groups of migrants being freely accepted in their new countries, Milanović observes that there are, within the current balance of factors, basically two pragmatic options: First “to accept de facto but not de jure a difference in treatment between the native-born population and a portion of the migrants while limiting the flow of migration.“ In other words, allow the de facto discrimination of migrants (arguably as is done right now) and limit migration because of the lacking popular support for the legal equality. The second pragmatic solution would make it possible “to allow for a larger inflow of migrants while introducing a legal difference of treatment between migrants and natives“ (M. 2016: 153). This would allow for the lacking popular support to be increased as the people arriving need to grow to their full access to the legal rights and privileges of living in a particular country.

According to Milanović, from the proposed economic and somewhat pragmatical point of view, the second option seems preferable, because we empirically know that increased migration contributes to an increase in global GDP and the incomes of migrants. Mild forms of discrimination might seem acceptable for migrants if the situation appears preferable to remaining in their countries of origin. Milanović makes it very clear that a discriminatory solution to the problem of discrimination of migrants is fundamentally weak and lacks appeal, but might be necessary to allow for an overall more consistent system and overall better treatment of migrants. Although one might understand where Milanović is coming from, one should seriously wonder whether it is a good idea to write policy to fit the current broken reality or whether better political and societal leadership is required to ensure the responsible and dignified human treatment of migrants. Should our bar come down to our level or should our societies reach for that higher standard? This is not to suggest that migratory regulations should not be imposed to make the influx of people manageable, at some fundamental level, but accepting as policy the fundamental discrimination of people, excluding them from services, care, and support which are recognized to ensure the personal dignity of every individual is questionable and possibly should be rejected. That being said, Milanović, even if we disagree, forces us to reflect on this very important and timely question.

3. Within-nation Inequality – an Extrapolation

As mentioned above, and as depicted in figure 1, global inequality slightly decreased from a global Gini value of 72.2 in 1988 to 67 in 2011. This is, as also mentioned above, due to the fast-growing economies of Asian countries like China, Japan, Singapore, and India. At the same time, within-nation inequality is increasing in many countries, as depicted with the US in figure 1. Milanović extrapolates this trend, indicating that questions of “class-based inequality” will grow in significance in the coming decades. To describe this process, Milanović introduces a theoretical approach formulated by the economist Simon Kuznets, known as a ‘Kuznets wave’ or ‘cycle’, and further mechanisms (malign and benign) that affect the mentioned wave/cycle.

Basically, a ‘Kuznets wave’ describes the relation between economic growth and income distribution inequality. He posits that in the process of economic growth, inequality will increase, but subsequently decrease, after a specific amount of time. The curve itself, depicting inequality over income per capita, would therefore look like a convex parabola (like a hill). With growing income (per capita) inequality rises but continues to decrease further along. Forces or mechanics which can bring the increase of inequality to a halt and decrease, can be differentiated in “malign and benign forces”.

Malign (harmful) forces occur through events such as wars, civil conflicts, revolutions, or epidemics, which may, like epidemics, happen independently of income distribution (a relation can be observed, for example, when poverty leads to neglect of hygiene in cities, resulting in the emergence or rapid spread of epidemics). However, civil conflicts, revolutions, and wars are often connected to social realities, in which inequality in income distribution does play a significant role (“most political battles are fought over the distribution of income“ M. 2016: 86). All the mentioned events can have ambivalent outcomes concerning inequality; they can either increase or decrease inequality or have no effect at all. Benign (harmless) forces, on the other hand, can be active steps undertaken by states, which contribute to redistribution, such as through social systems or financial support in education, etc. (see. M. 2016: 55f.). Milanović (2016) demonstrates the significance of both mechanisms/forces through an analysis of preindustrial societies with a stagnant mean income. Following Kuznets’ hypothesis, in a situation of stagnant mean income, no relationship with inequality can be observed. Inequality changes while the mean income remains constant, therefore Milanović (2016) argues, that “inequality expands and contracts in preindustrial economies against a broadly unchanging mean income, driven by accidental or exogenous events such as epidemics, discoveries, or wars“ (M. 2016: 69).

Entering an analysis of postindustrial states, Kuznets’ hypothesis on the relationship between income per capita and inequality has been critically reviewed. While we would expect inequality in countries experiencing a post-World War II increase in mean income, such as Great Britain, the US, the Netherlands, etc., to decrease, we observe a continuing rise, which prima facie seems no longer explainable by Kuznets’ hypothesis. Milanović (2016) therefore speaks of a second ‘Kuznets wave’ beginning in the early 1980s linked to the technical revolution occurring with changes in the most dominant sectors of economy (like for labour – a transfer from manufacturing activities to services, etc.), and resulting out of progress in information technology and globalization. Taxation became more difficult because of a increase in mobility of capital, leading to marginal taxation on the highest incomes, or “in other words, the redistributive function of the modern developed state has either become weaker or remained more or less the same as in the 1980s“ (M. 2016: 107). Income inequality within rich countries is rising from the 1980s onwards. This upward trend leads to growing tensions, as Milanović argues: “A very high inequality eventually becomes unsustainable, but it does not go down by itself; rather, it generates processes, like wars, social strife, and revolutions, that lower it“ (M. 2016: 98). That’s the malign forces mentioned above and “very often in history, it has been precisely the malign forces of war strife, conquest or epidemics that have reduced inequality“ (M. 2016: 113).

Milanović therefore supposes five benign forces that could lead to a downward portion of the second ‘Kuznets wave’:

- Political changes, that favor higher and more progressive taxation.

- The race between education and skills. Currently we observe a skill-bias in labor due to technological changes, further leading to a rising supply of highly skilled workers, which has a natural limit.

- The dissipation of rents accrued in the early stages of the technological revolution (like stocks in financial, insurance and IT sectors).

- Income convergence at the global level.

- Low-skill-biased technological progress, meaning technological changes that would favor unskilled workers more than skilled.

4. New Capitalism, Plutocracy and Populism

In the closing of his book Global Inequality, Milanović tries to extrapolate or predict some main expectations for future developments in (global) inequality. Before doing so, he clearly marks that predictions are somewhat problematic and have, in most cases, been wrong in the past.

His predictions are based on “two powerful economic theories” (Milanović, 2016: 161) which were already mentioned earlier. Further globalization will lead to greater “income convergence,” meaning that poor countries will catch up with the rich world concerning mean income, as we have witnessed and are still witnessing in China, India, Indonesia, etc. This increase will further occur in more and more countries and will, at some point, slow down, as is already visible in China. In addition to this catch-up process, Kuznets waves are important for understanding the evolution of inequality within states. Some of the examples mentioned are beginning to climb the first ‘Kuznets wave’, meaning the inequality within these states is increasing, but it will eventually start to decline, as we are starting to see in China. Rich countries, which are climbing the second ‘Kuznets wave’, “may go further up the rising portion […] (as I think the United States will; […]) or may soon start on its downward portion” (Milanović, 2016: 162).

For the United States, Milanović speaks of a “new capitalism“ which means that the division between capital and labour is decreasing – they have started to overlap. Unlike in classical capitalism, “rich capitalists and rich workers are the same people“ (M. 2016: 187). One practical problem arising out of this situation is that it is more difficult to criticise, or to “tackle ideologically and politically“ new capitalists, because “many of them are highly educated, hardworking, and successful in their careers“ (M 2016: 188). This situation is reinforced by the fact that, as demonstrated by Milanović through studies, people tend to marry within the same social strata. Individuals who are also well-educated and have been able to position themselves well economically thereby form “equal partnerships“. Furthermore, the political system in the United States contributes to the entrenchment of inequality. Election campaigns require a lot of capital; therefore money plays a significant role in determining who can win an election. Studies suggest that most decisions made, and laws passed, favour a wealthy class (he refers to studies by Larry Bartels, among others). The political system is much more responsive to interests of “people at the 90th percentile of income distribution“. (M. 2016: 189). A positive feedback-loop is created, where “pro-rich policies further increase the incomes of the rich, which in turn makes the rich practically the only people able to make significant donations to politicians“ (M 2016: 190). He speaks of a “plutocracy“ which “is thus born“.

Milanović points out that a decline of the economic power of the middle class is visible, most salient in the United States but also in all advanced economies (“the top 5 percent in the United States have almost as much income as the entire US middle class“ M. 2016: 197). This decline goes hand in hand with a decrease in political representation of the interests of the middle class, further leading to growing class-separation. Within this situation Milanović sees a possible slide away from democracy, occurring in two forms: as plutocracy in the United States and as populism or nativism in Europe.

Plutocracy means in Marxist terms a “dictatorship of the propertied class“, which sounds a bit harsh in this context. But as mentioned, “elected officials are responsive almost solely to the concerns of the rich“ (M. 2016: 199). The amounts of private money in congressional and presidential election campaigns are growing, while the participation of the middle class in elections is decreasing (“80% of people in the top income decile vote, compared with only 40% in the bottom decile“). Another aspect that comes into play is ideologically charged political discourse, creating what Milanović calls “false consciousness.” Public media debates tend to focus extensively on issues like religion, abortion, and similar topics, while rarely addressing concrete social questions and problems.

In European multiparty political systems, money and the associated plutocracy play a less significant role. However, problems with migration and the decline of the welfare state are leading to dissatisfaction with current political systems. In addition to the growing number of migrants, European states face “serious problems in assimilating migrants” (M. 2016: 205) who have been citizens for several generations. One impact of this issue can be observed in the “creation of ethnic ghettos” (ibid.) around European cities like Paris. This problem cannot be solved solely by governments, as it involves interactions between people from different religious and cultural backgrounds. However, governments can create a supportive environment that fosters these interactions. They can prioritize issues concerning ethnic minorities and social problems on their political agendas, promoting policies that facilitate integration and mutual understanding. The depicted situation, mainly the crumbling of the welfare state and of “left and mainstream parties“ has given populist parties a way to position themselves. Consequently, we can observe growing participation of populist parties in most European countries.

Even though Milanović argues that it is quite unlikely for one of these parties to come to power on their own, they have changed and are further changing and shaping the European political landscape (the UK leaving the EU would be a notable example). He argues that populist parties are undermining democracy by “gradually revoking or redefining some fundamental rights of citizen“ (M. 2016: 210). Populism, in Milanović’s view, “represents a retreat both from globalization and democracy“ (ibid.). In a nutshell, he summarizes: “plutocracy tries to maintain globalization while sacrificing key elements of democracy; populism tries to preserve a simulacrum of democracy while reducing exposure to globalization“ (M. 2016: 211).

Conclusion

Milanović points out that “For the first time in human history, a system that can be called capitalist, defined (conventionally) as consisting of legally free labor, privately owned capital, decentralized coordination, and pursuit of profit, is dominant over the entire globe” (Milanović, 2016: 192). Globalisation confronts us with many challenges on various levels. In addition to economic and political aspects, social and cultural questions also come to the forefront. However, we cannot close ourselves off from these processes. When it is said that we are living in a “time of crisis,” with issues such as climate change and global warming, the production methods of consumer goods, migration, etc., we quickly realize that these “crises” scale globally and increasingly affect us as humanity, not us necessarily as Austrians, French, or Japanese, even though there might be differences. On the other hand, questions arise regarding how we can understand ourselves as living in nation-states, as this understanding of homeland and origin is important for the construction of people’s identities. We notice that in precarious times, strong narratives resurface, which distinguish the familiar/the native from the foreign. How to maintain cultural diversity in a globalized and interconnected world is a challenging question that we must begin to address. To share a personal impression, it seems to me that we shy away from thinking on a highly complex, broader, or even global scale, and thus fall into a fragmentation that cannot do justice to the globalized world, in which we already live.

Milanović’s publications provide a good starting point to delve into the complexity of global economic interactions, even for an economic novice (like myself). I found his views on migration to be discussable, interesting and innovative, as well as his prognosis regarding the growing significance of the class issue within states and correlating shifts in labor (importance of education; new capitalism). However, in many instances, there is a lack of more extensive elaboration or discussion of his proposals, which often imply significant social and political questions. While Milanović’s work is invaluable in highlighting the pressing issue of global income inequality, critics argue that a more comprehensive exploration of the practical implications and potential policy solutions is necessary to fully appreciate and address the complexities involved. Nonetheless, his contributions remain crucial in advancing the discourse on economic disparity and informing future research and policy development.

Bibliography

Hickel, Jason: The Divide: A Brief Guide to Global Inequality and its Solutions. London: Heinemann. 2018 (https://eddierockerz.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/the-divide-a-brief-guide-to-global-inequality-and-its-solutions-pdfdrive-.pdf)

Milanović, Branko: Visions of Inequality: From the French Revolution to the End of the Cold War. Cambridge/London: Belknap Press. 2023

Milanović, Branko: Global Inequality. A new Approach for the Age of Globalisation. Cambridge/London: Belknap Press. 2016

Milanović, Branko: Worlds Apart. Measuring International and Global Inequality. Princeton/Oxford: Princeton University Press. 2005

Vries, Peer: Escaping poverty. The origins of modern economic groth. Göttingen: V&R unipress. 2013

Wagenknecht, Sahra: Die Selbstgerechten. Mein Gegenprogramm – für Gemeinsinn und Zusammenhalt. Frankfurt am Main: Campus. 2021

Online Sources

World Bank Gini index: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SI.POV.GINI?end=2023&most_recent_value_desc=false&start=2023&view=map

About the Author/Editor:

Simon Elias Unteregger has a background in German studies, biology, and philosophy. He is currently pursuing a Master’s Degree in German studies at the University of Salzburg.

Johannes J Knecht completed his BA in Theology and Biblical Studies at the Evangelische Theologische Faculteit (Belgium). He completed his MPhil and PhD in Systematic and Historical Theology at the University of St Andrews (UK). Besides his work with the Quo Vadis Institute, Jasper also teaches Christian doctrine at WTC Theology (UK).

Featured Image: Verena Schnitzhofer